WP90X Recap – ESOPs: A Different Way of Selling to a Third Party

Published: July 25, 2025

In our June WP90X webinar, WealthPoint’s Michael Kenneth and Drew Schaefer of SCJ Fiduciary Services outlined how ESOPs function, when they make sense and how they can be structured to maximize both value and legacy.

This recap distills the key insights, dispels persistent myths and encourages owners and advisors to consider ESOPs as a serious, tax-advantaged path to exit.

Interested in learning more? Dive into the presentation slides or keep reading as we hit the key points.

Why ESOPs Deserve a Second Look

Too often, ESOPs are dismissed due to misconceptions. Some owners assume they will receive less than fair value. Others believe they will lose control or hand the company over to inexperienced hands.

The truth is ESOPs are structured, regulated transactions governed by ERISA law. Independent trustees and third-party valuation firms ensure the seller receives fair market value. When structured well, an ESOP can deliver liquidity for the owner, tax efficiency for the company and long-term wealth creation for employees, all while maintaining operational continuity.

How the ESOP Structure Works

Mechanically, ESOPs resemble a leveraged buyout. The company borrows funds, loans them to the ESOP and the ESOP uses that capital to purchase stock from the owner. Employees do not buy in directly—instead, they accrue shares over time as part of a retirement benefit plan.

The company repays the internal loan over time using pre-tax dollars. As that loan is paid down, ownership shares are released and allocated to employees according to payroll and tenure.

This structure allows business owners to achieve meaningful liquidity while keeping leadership in place and preserving the company’s mission and identity.

The Tax Advantage That Changes the Game

For 100% ESOP-owned S corporations, federal income tax effectively disappears. Because the ESOP trust is tax-exempt, the company’s profits pass through without triggering federal tax liability. That additional cash flow can be reinvested, used to pay down acquisition debt or distributed through other strategic means.

On the seller’s side, the IRS §1042 rollover provision can allow for deferral—or even full elimination—of capital gains tax if the sale is properly structured and proceeds are reinvested in qualified replacement property. While not available in every situation, this planning tool can add substantial after-tax value to a transaction.

What Happens to Control?

One of the most common questions is, “Who is in charge after the ESOP closes?” The short answer: Often, the same people who were in charge before.

Post-sale, shares are held in a trust managed by an independent trustee. Employees are beneficial owners, but they do not receive direct control or voting rights. Leadership typically remains with the current executive team, and corporate governance is maintained by the board of directors, often with the addition of one or more independent directors for objectivity and compliance.

An ESOP can offer liquidity and transition ownership without requiring the founder to exit immediately or fundamentally change how the business is run.

Busting the Top ESOP Myths

In our collective experience, these are the myths we have most commonly encountered surrounding ESOPs.

Warrants, Phantom Equity and Smart Planning

Well-designed ESOPs also support long-term planning and alignment at the leadership level. Sellers can retain upside through warrants, allowing them to participate in future appreciation of the business—sometimes referred to as a “second bite at the apple.”

Similarly, synthetic equity tools like phantom stock or stock appreciation rights (SARs) can be used to retain and motivate key executives without diluting ownership. These mechanisms are particularly valuable for aligning the management team with the company’s long-term growth post-transaction.

With the right structure, ESOPs can balance succession planning, tax strategy, leadership retention and company performance.

Is Your Company a Good Fit for an ESOP?

While ESOPs offer many benefits, they aren’t the right solution for every business. Common traits of ESOP-ready companies include:

- $3M+ in EBITDA and/or $20M+ in revenue

- 25 or more full-time employees

- Consistent profitability

- Strong leadership and organizational structure

- Industry alignment (e.g., construction, manufacturing, distribution, professional services)

The best next step is a feasibility analysis. At WealthPoint, we help owners understand how an ESOP might work in practice—financially, structurally and operationally—before making any commitments.

Custom-Build the Right ESOP with WealthPoint

If you are planning a transition in the future, or advising someone who is, ESOPs should be part of the conversation. They provide a path to liquidity without giving up control, deliver meaningful tax advantages and help preserve the values and culture that made the business successful in the first place.

To explore whether your business is a candidate for an ESOP, book an expert-led planning session with the WealthPoint team. We will walk through the financial modeling, deal structure and long-term strategy, so you can make an informed, confident decision.

Thank you for your interest in ESOPs, and we look forward to discussing this powerful tool with you!

Full Webinar Recording and Transcript

Michael Kenneth (00:00)

Good morning everybody. This is Michael Kenneth with WealthPoint. Thank you all for joining us on today’s session regarding Employee Stock Ownership Plans, ESOPs, which are really a different way of selling to a third party. I’m really excited about today’s presentation. I know ESOPs in the marketplace have become much more common, specifically out here in the Southwest in Arizona seems to be one of the hottest markets at the moment for Employee Stock Ownership Plan transactions.

We’re really excited to go through an educational session, really talk through kind of the ins and outs of ESOPs and also hear from my co-presenter today, Mr. Drew Schaefer. And so Drew, maybe if you wouldn’t mind just giving a brief introduction to yourself and your firm SCJ Fiduciary Services. And then we will get started on some specifics and go through the presentation.

Drew Schaefer (00:56)

Thanks, Michael. Yeah, I’m Drew Schaefer. I’m an individual trustee located right outside of Louisville, Kentucky. And so myself and four other trustees work with a firm called SCJ Fiduciary Services. So we have 25 team members all across the country. And we support over 325 ESOP companies.

And actually, I got my first start and exposure in working for an ESOP company and saw the great benefit that was to the employees as participants and just what a great wealth transfer tool it is.

Michael Kenneth (01:35)

Awesome, perfect. I appreciate that Drew, and I’m excited to later on in our presentation when we go through a little bit of a Q&A session with yourself. I know there’s a lot of questions that come up regarding trustee involvement, trustee control, board control, those types of things as it relates to ESOP transactions. I think there’s a lot of misnomers that are out there in the marketplace on that. And so excited to be able to ask you some direct questions and learn a little bit more.

Drew Schaefer (01:57)

Looking forward to it.

Michael Kenneth (01:58)

So just a couple of housekeeping items for everybody that’s attending today. We are offering credit or CE credit for CPAs and CFPs. So we will have, again, this is a recorded webinar. We will have polling questions. Don’t worry though, that third sub bullet is the most important one. You’re not graded on right or wrong answers. Just make sure that you do answer them in order to get the credit.

If you do have questions that come up throughout today’s webinar, feel free to interject and ask. We do have a Q&A function on your Zoom toolbar that you can use to ask any questions. I would definitely appreciate questions as they come up. Drew and I both talked about it and want this to be as interactive as possible with all of you this morning. So if there are questions, feel free to raise your hand and ask those and we’ll get those addressed timely as we see them come up.

If you do have any questions on the webinar, technical issues, anything like that, you can reach out to my colleague, Kristin, Kristin@wealthpoint.net, and she will help to answer any questions that you guys have. And then lastly, after the webinar, we will be circulating a survey. Appreciate any open and honest feedback, as long as it’s positive. Just kidding there. But appreciate you guys completing that survey. Once you complete that survey, we will prepare your CE certificates and get those sent back out to you guys.

With that, we’ll go into the learning objectives for today’s session. Again, it’s all about ESOPs, how they work, why we use them, why would we pick an ESOP versus say a different exit strategy, a third party sale, internal succession, something like that. We’ll talk about the impacts of the company and its employees as well as the selling or the exiting shareholder.

Michael Kenneth (03:47)

We’ll talk through the tax benefits for an ESOP, how they can help to repay company debt, methods for deferral of taxation by using an ESOP as a exit tool or an exit strategy. Talk about bank debt warrants, ESOP share allocation, which will go through kind of a model of how that’ll look. And then really learning about the ESOP trustee process and giving Drew a chance to kind of explain it, you know, not from a necessarily company or a seller point of view, but from the alternative point of view, right, as the buyer, if you will, or as the individual or the group that’s representing the buyer in the ESOP transaction.

You know, how do they do it? What does control look like? Those types of things as we go through it. And yeah, just first, I got our first question, which I’m already a big fan of. Love the interaction here. Russell asked us, will the slides be available after the webinar? Yes, they will. So we will circulate a copy of this recording and post the slides, we’ll have a link to our website and we’ll get all that posted so you guys will have access to it after the webinar.

So as we kind of dive in here, just from taking a real cursory overview of ESOPs or Employee Stock Ownership Plans, what they really are is a benefits plan designed to create an employee stock ownership trust which acquires shares of the company. Either they purchase the shares directly from exiting shareholders or they purchase shares directly from the company through a subscription process.

And it allows an exiting owner to monetize their ownership. They still have a level of control through board governance, which we’ll talk about a little later on in the presentation. And then obviously providing a huge economic benefit to all of the employees. Drew just mentioned earlier, but it is one of the most significant wealth transfer tools that are available for business owners to transfer wealth to their employees. So if we look at it from an employee’s perspective, just to start, the stock that’s held in the ESOP is allocated to the employees over time. Usually that allocation is based on either compensation, years of service, or some sort of combination of both. And we’ll actually go through an example of how that looks a little later on in the presentation. But effectively each and every year there’s a mechanism, a process, excuse me, to allocate those shares to the employees.

Michael Kenneth (06:03)

The employees then receive a statement each and every year that shows how many shares they have, how many shares were added to their account, what’s the price per share, and therefore what’s their account balance worth, and also what is vested into their account balance based on the vesting schedule of the plan. The employees then have the ability to monetize their shares based on certain triggering events. They’re the most common triggering events that you see in regulated plans, death, disability, retirement, termination, change of control.

Effectively, any time an employee leaves the company in a more formal fashion, that results in a triggering event. An employee then has the ability to monetize those shares through the process that’s defined in the ESOP plan document. And typically, those payments are made out over five years. So just as a very simple example, if I’m an employee, I have $500,000 of equity value in my account, and I retire at 65, I’m going to get roughly 100 grand a year for the following five years.

Sometimes that can be accelerated, in other situations that extended out. It just depends on the facts and circumstances of the overall ESOP and the structure. The one comment that I’ll make just on ESOPs from a very high level, we actually kind of laugh about it internally all the time, but once you’ve seen one ESOP, you’ve only seen one ESOP. Every structure is different. Every transaction’s different. How the documents are drafted, how the ESOP plan is administered, it all varies company to company.

And so what we’re gonna go through is a real, you know, general overview and educational session on ESOPs, but each individual ESOP, I know Drew, you and I have had a chance to work on several transactions together and they’re somewhat closely related, but most of the time drastically different, right? In terms of structure, purchase price, share allocation, plan provisions, etc.

A couple other factors on ESOPs. All full-time employees must participate in Employee Stock Ownership Plans. One comment there is the definition of full-time is a thousand hours or more. That’s governed or that’s regulated, I should say, by the IRS and the Department of Labor. So if you work more than a thousand hours per year, you’re typically eligible to participate in the ESOP. The ESOPs are also non-discriminatory plans.

Michael Kenneth (08:21)

So you cannot, as a company, select, I want these five employees to participate in the ESOP, but not these five, right? It’s based on number of hours, based on years of service, based on your age as an employee, you define those characteristics in the plan document. If you fit those characteristics, you’re automatically eligible and enrolled into the plan to participate.

And then, from a high level, ESOPs operate very similarly to 401Ks or profit sharing plans in the sense that they are, you know, a qualified plan, the growth on the value of the shares while they’re held in the ESOP is tax deferred. Meaning if the company value grows from 20 million to 30 million over a period of time, that growth on the shares that are held in the ESOP is tax deferred. There’s no taxes that are paid out on those shares on an annual basis. But when the employees monetize, when they get paid out for those shares, that does become a taxable event. It’s treated as ordinary income for them when they receive it.

One comment I’ll make too on that is that the employees do typically have a rollover provision. So they could roll some of these proceeds over into other qualified plan assets if they choose to. The primary difference though, between say, ESOPs and other qualified plans like a 401k or a profit sharing plan, and really there’s two differences.

First, most of the time employees do not defer compensation to buy shares in an ESOP. They’re automatically granted those shares or allocated those shares based on the share allocation formula, but they’re not deferring comp to acquire shares. And then the second aspect is in an ESOP, it’s primarily invested in the company, right? It’s an equity shareholder in the company. It is not an entity where you’re picking other mutual funds, other investments and allocating those shares.

Drew, sorry, I just wanted to pause. I got a question that just said that he can’t hear anything. Can you guys hear me? I can. Okay. Well, that’s good to know. I was hopeful that I wasn’t just going on and on there and nobody heard anything. So appreciate that comment there. as we, first off, just a perfect thank you guys. Appreciate it. Glad everybody can hear me. First question, first polling question, you’ll see it pop up on your screen here.

Michael Kenneth (10:38)

So go ahead and make sure you answer that just so that you get CE credit as we continue through the webinar. Next slide here I want to focus on is just who’s all involved in an ESOP transaction. Sometimes these entities or these individuals are involved just for the transaction purposes. Other times they are involved on the long-term. First and foremost, you have the company and its shareholders, right?

One comment that I’ll make that we’ve actually done this strategy before is not all shareholders have to participate in the sale to the ESOP. Now, obviously that is only if you’re not doing 100% sale. If you’re doing 100% sale, everybody’s participating. But if you’re doing anything less than that, then you actually have the ability to, you know, one shareholder can keep all their shares, the other shareholder could monetize their shares.

So this can be a really great strategy if you’re looking at say like a partnership buyout, or potentially maybe pruning the family tree, if you will, in family held businesses. So instead of having your partner buy shares, company redeem shares, whatever that looks like, you could create an ESOP that now is a 30% shareholder, a 40%, a 60%, whatever that percentage is.

You have a trustee as well, i.e. Drew Schaefer, typically hired by the company to represent the employees in the transaction and also serve on an ongoing basis. We’re gonna get into more detail later on in the presentation of what that role really looks like and how Drew and his team really approach transactions, as well as the ongoing management. But the comment that I’ll make there again, is just to make sure you have an individual independent trustee, somebody who’s independent from the transaction. I think that’s been a shift in the ESOP marketplace over the last.

I don’t know what you said, Drew, maybe five, 10 years, something like that of moving more towards independent trustees as opposed to internal trustees. Is that a fair statement?

Drew Schaefer (12:37)

Yeah, I’d say when the process, what’s called the process settlement agreements came out right around 10 years ago, that’s when the demand for our services really went through the roof.

Michael Kenneth (12:49)

And I think, you know, from an outside perspective, it seems very common sense that you should have an independent party represent the employees in an arms length transaction. But as Drew mentioned prior to that process settlement, it was very common to have internal trustees, i.e. the CFO was serving as the trustee to try to negotiate an arms length transaction with the shareholder who, by the way, that CFO’s typically the boss or or primary owner of the company, right? And so there was obviously an inherent conflict of interest.

However, the process settlement really changed that. And now we really only work primarily with independent third-party trustees as opposed to internal trustees. You have legal counsel as well, both on the buy side representing the trustee or the ESOP, and then on the sell side representing the company and the shareholders. You have a valuation firm that’s somebody or a group that’s usually hired by the trustee to perform an independent valuation of the business.

The trustee relies on them to help to negotiate the purchase price, determine the fairness of the transaction, issue a fairness opinion at the conclusion of the transaction. And then I would say probably 90% of the time, and maybe even higher, that same valuation firm is engaged ongoing to perform the annual valuation to determine the price per share for the employees and the share allocation. A third party administrator at TPA to manage really the compliance aspects of the ESOP

Commercial bank or obviously if we’re doing any bank financing, allowing the shareholder to take some chips off the table. And then lastly, our services, we act as a sell-side advisor to really help oversee and structure the transaction, right? Guide the process forward, do the feasibility analysis, negotiate the transaction and really become an employee owned or an ESOP owned company.

Michael Kenneth (14:44)

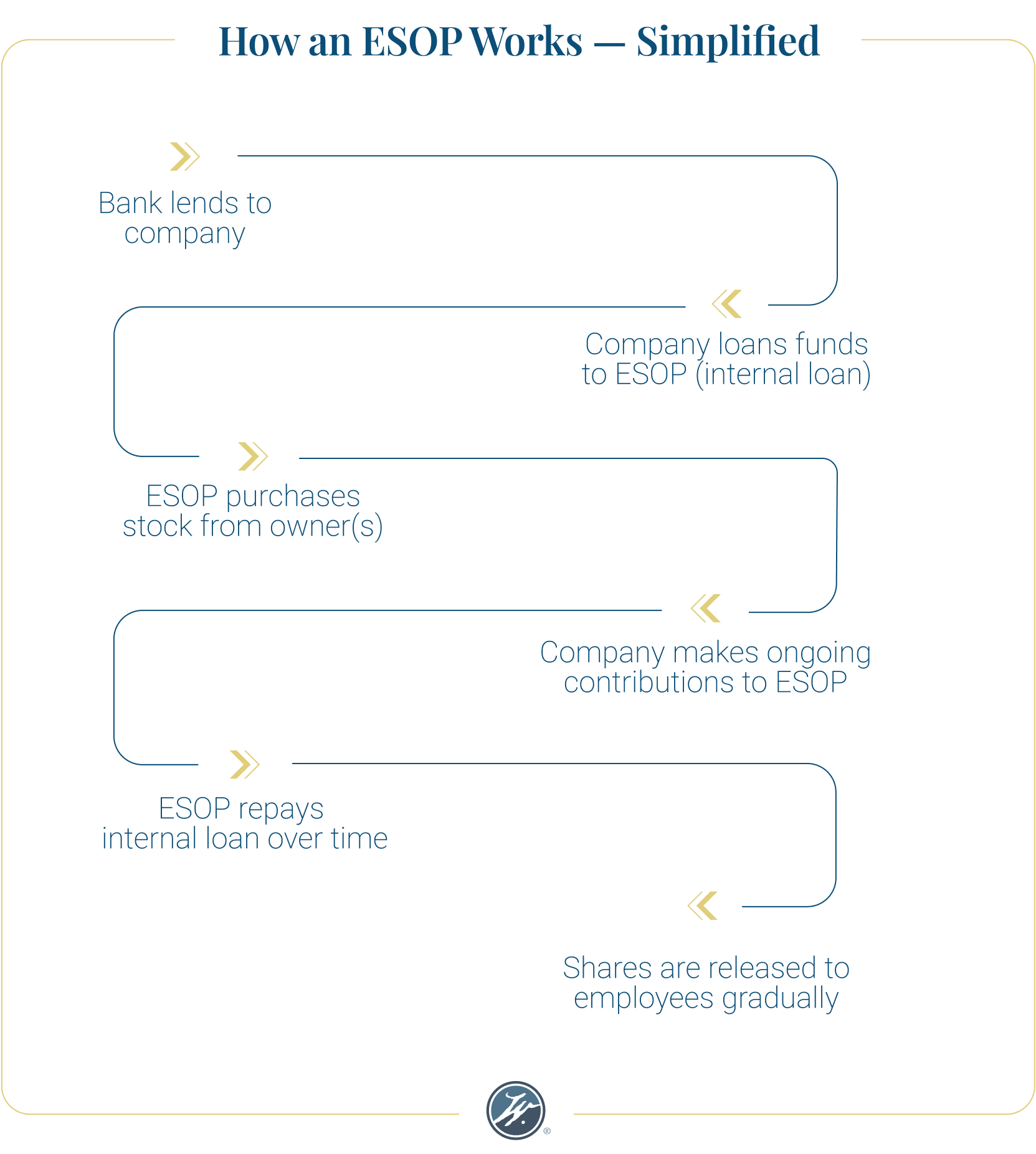

So when we just track the flow of money for an ESOP, and as I mentioned earlier, you know, once you’ve seen one ESOP, you’ve only seen one ESOP. But this just gives a high level example of the flow of money and how things are structured. So in this case, we have four stakeholders that are involved, the bank, the company, the ESOP and the shareholders. Typically, the first step in that process is the company is going to borrow money from a bank. They go out to their existing relationship or to a new relationship and negotiate to really just get a term loan.

What we’re seeing in the marketplace today, is that most of the terms on those term loans are usually five, maybe seven years. Amortization period is probably seven to 10 years. The interest rate tracks the interest rate environment, typically follows an index with some sort of a spread based off of the company’s financial strength and solvency. And they’re negotiating for that transaction.

The one comment that I would have for all of you as advisors is to make sure that if your company, if your client is going through an ESOP transaction with a bank that’s involved, you want to make sure that bank is familiar with ESOPs because the accounting is different. The definitions are different. There’s, you know, ESOP adjustments that happen on the financials. Just want to make sure your bank is, you know, really knowledgeable in that area as it relates to financing for ESOP transactions.

Step two is the company takes those funds and loans them to the ESOP. This is what creates what’s called the internal loan, which I’ll explain in just a second why that’s important. But the primary reason for that is that way you have the ESOP that now has the cash. The ESOP takes that cash and acquires the shares or the equity from the shareholders based on the purchase price that’s been agreed to. And then in most situations, you have some form of a seller note.

As an example, let’s say that we have a $30 million business. A bank loans $12 million to cover a portion of that purchase price, i.e. 40%. The other 60% becomes a seller note, and that gets paid back over time, principal and interest, based off of the terms of the transaction.

Michael Kenneth (16:59)

The reason, just one comment on this, the internal loan structure of this step two, the reason why that’s important is because when we look at it post-transaction, the company has its obligations, right? It needs to pay back the bank. It needs to pay back the seller note as a result, again, of the terms that have been agreed to in the overall structure. At the same time, the company is making contributions or distributions to the ESOP to then fund the repayment of that internal loan. In other words, step two, company makes a contribution. Those contributions can be made up to 25% of eligible payroll.

Keep in mind, 401k contributions, other deferred comp type structures or qualified plan structures, those all fit into that 25% bucket for the limitation on deductibility there. But the company makes those contributions every year, ESOP takes receipt of that and then sends it right back to the company to make an internal loan repayment. While the company does this transaction and this kind of circular reference here of the money, the reason why that’s important is because as that internal loan gets paid off, that’s how shares are then released and allocated to the employee accounts.

And so this is a really key facet of ESOPs and how the employees actually get shares allocated to them. But it’s also something to be really mindful of. I’ve seen a lot of ESOPs that have happened where they have mismanaged that internal loan. Either they’ve paid it off too quickly, not paying it off fast enough, not using contributions or distributions.

And so if you have a company that is an active ESOP, you just want to make sure that they’re fully understanding that process because it’s critical to adhere to the terms of the transaction. Otherwise you’re going to run into a potential issue down the road. The other comment on this is that this is very important because over time you want to make sure you’re putting enough cash into the ESOP to be able to fund that repurchase obligation at some point in the future.

For the first few years of the ESOP, that’s somewhat of a very minimal issue because there’s only a small amount of shares that are being allocated over time. But as you get into more mature ESOPs, more developed ESOPs, year five, year seven, year 10, that repurchase obligation becomes a much more significant factor from the overall structure for the ESOP and the share allocation and managing cash. Drew, just a quick question for you on the internal loan aspect. Is that something that the trustee team typically manages in terms of notifying the company to make the payment, tracking the cash, what does that process typically look like from a trustee’s perspective?

Drew Schaefer (19:28)

Yeah, I think back before the process settlement agreements, it’s typically in and out. And so there was a lot of ESOP companies that would just kind of journal entry instead of actually moving the cash. So that’s very much frowned upon. And that’s one of the things that we help our clients with. The majority are 12, 31 year ends. And that’s typically when that payment’s due.

So we give notice to our clients in November, making sure they know the amount, talk about timing, especially at the end of the year with so many people out on vacation, we work to coordinate with them so that we can process the payment back to the company seamlessly. So if it’s part of their working capital that they’re not missing out on their working capital unnecessarily, if they have to go into a line of credit that they’re not incurring unnecessary interest fees on that as well.

Definitely something that we help facilitate.

Michael Kenneth (20:28)

Awesome. Perfect. And Drew, you brought up a really good point. And just to clarify for the group, that process, that contribution or that distribution, and then the returning payment, that typically is the exact same dollar amounts. So you make a contribution of $100,000 based off of the plan, the size, the transaction structure. ESOP trustee, i.e. Drew, takes receipt of that. Sits either for a day or maybe just a few hours, and then immediately is sent back that same $100,000.

And so from a company cash perspective, it is just an in and out, right? Or I should say, guess an out and in would be a better way of describing it, right? But the cash balance doesn’t change as a result of that, right? And so I think that’s just important to recognize for companies that yes, we are moving money around and creating the structure to release shares and maintain compliance with the ESOP, but it’s not that we’re sending out 100 grand and getting 10 grand back.

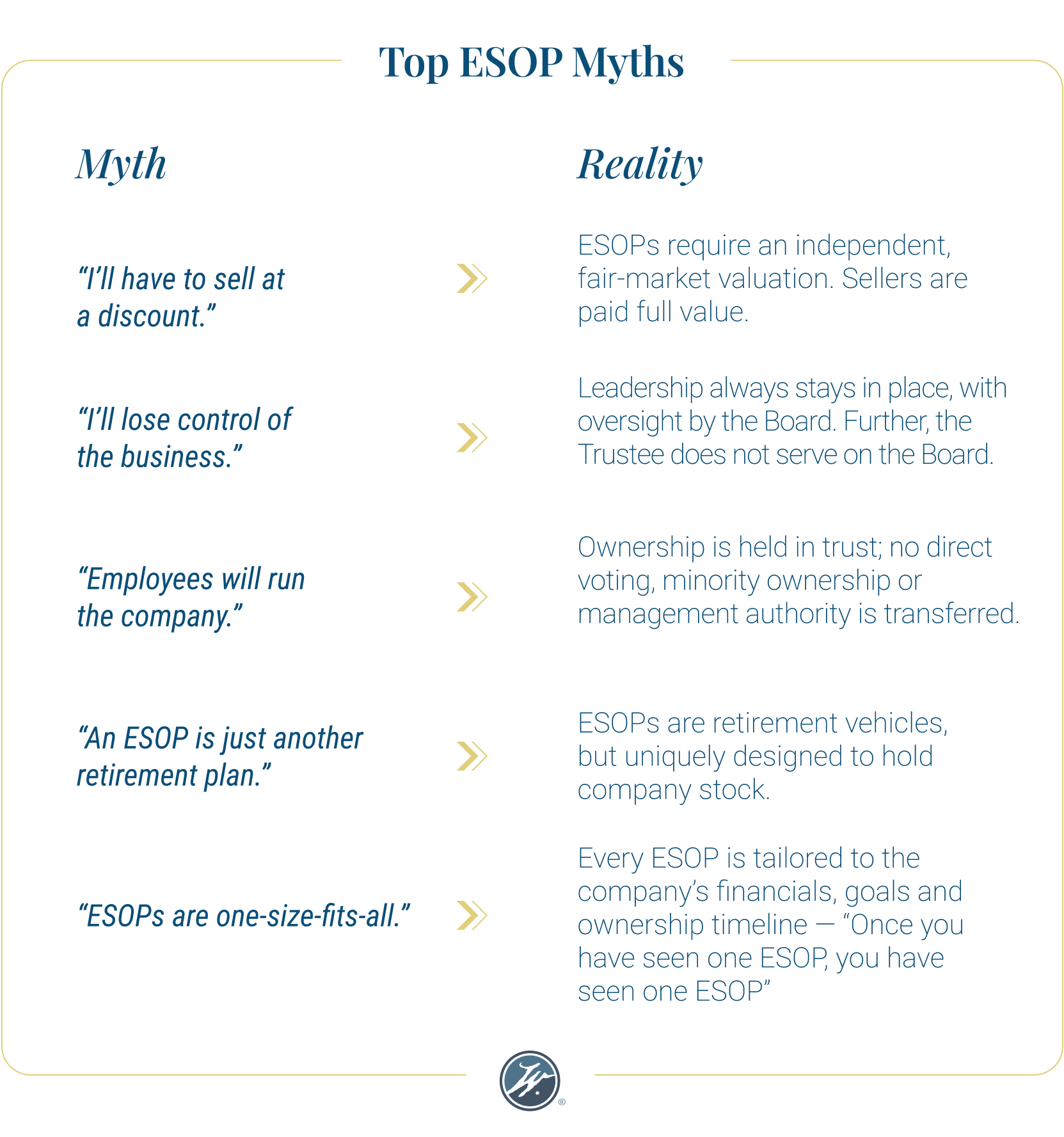

Right. We were sending out a hundred grand and having that come back in future years, we may have to put more money in to manage that repurchase obligation. But obviously at that point, we’re typically debt free or something like that much further out into the future. So next slide here just looks at some ESOP inaccuracies, ESOP myths, those types of things. When you research ESOPs, just like primarily anything in today’s society, you get polarized views, right? ESOPs are really great. ESOPs are really terrible.

We just want to sort through a few of the key ones here. I’m not going to read through every single one for you guys today, but just a couple of the key ones that I think we want to focus on. First one is very important from a shareholder perspective. Some people think that when you sell to an ESOP, I’m selling to my employees, so therefore I have to sell for less than fair market value. I have to take a discount, right? It’s my employees, they should pay less than fair market value.

And that’s false. And it’s really false for two reasons. One, there’s regulation that states that it should, it has to be for fair market value. You can’t take a discount. You run into other tax consequences or other issues there if you do. But secondarily, there is an independent third party valuation that’s performed and they establish a fairness opinion and they support the purchase price. The other comment, and we’ll hit on it a little bit when we talk about the trustee process, but it is an arm’s length transaction.

It’s not, hey, the valuation firm said the company is worth $50 million, so we transacted that, right? There is a back and forth. It’s price and terms. And so it’s just important to recognize that, you know, ESOPs, think, relative to, third-party sales, are a more controlled transaction. We’re creating the ESOP. We’re creating the transaction team. We’re able to really control the aspects of the transaction.

Michael Kenneth (23:11)

But it still is a third party transaction, still is a back and forth. Drew has a fiduciary responsibility to negotiate in good faith for what the ESOP can afford or transact at, just like the sell side advisor negotiates in good faith to get the company and the shareholder the best result that they’re looking for as well. The second one is important as well. Some people think that if you sell to an ESOP, the trustee takes over, right? They run everything, they do everything.

They make all the decisions, etc. And that’s false as well. Trustee really represents the employees in a fiduciary capacity, primarily to negotiate a fair transaction on their behalf, but they don’t want to be involved in terms of running the day-to-day operations of the business. Drew mentioned it earlier. They have 300 plus companies that they are serving, his company is serving as trustee for. That would be ridiculous in terms of the volume of work if you had to make all of the decisions, right?

We’ll hit on board governance, trustee oversight, those types of things in just a second, but I wanted to hit on that as a key point as well. And then the third one up here as well, just employees, you some people think when you become an ESOP, the employees get to make all the decisions and that’s categorically false as well. And the reason why is because employees don’t hold the shares.

They simply have beneficial ownership in a trust that actually holds the shares. So even though an employee might own a hundred shares, 500 shares, 3000 shares based off of their ESOP account and what’s been allocated, they don’t actually have the stock certificates, right? They’re not minority shareholders. They don’t have any minority shareholder rights. They don’t see financial statements and tax returns, nor do they have any operational control or decision-making leadership management, etc.

In fact, we’ve had a few ESOPs that we’ve done where we’ve transacted and they’ve waited three, four, even six months before they tell all of the employees that they’ve become an ESOP. And the employees are shocked because nothing changed, right? Operations, management, leadership, all of those types of things. know, it’s not a, everybody gets to make every decision. So just wanted to hit on a couple of those. Again, there’s some other key things in here. I think the last one is also, you know, really important.

Michael Kenneth (25:28)

Just that ESOPs are a viable succession planning strategy for the right business. We’ll hit a little bit later on about just the ideal client profile. But again, ESOPs can really work for companies depending on the facts and circumstances and the objectives. So with that, we have another polling question. So just keep an eye out for that on your screen here. And go ahead and answer that so you get your CE credit. Just for the sake of time, we’re going to keep on rolling here with the presentation and hit a little bit on the income tax benefits.

This is probably the most important aspect from a selling shareholders perspective of why companies are really focused on doing ESOPs. And the reason why is there’s really two different tax benefits that are available for employee owned companies. The first one is that ESOPs are tax exempt entities, right? They’re a qualified plan structure. They’re a tax free entity. They don’t pay any taxes on the growth of their shares. And so if you have an S-corp that’s a flow through entity, and the ESOP owns 100% of the outstanding stock of that S corporation, you have effectively mitigated all federal and for the most part, state income taxes on the company’s profits.

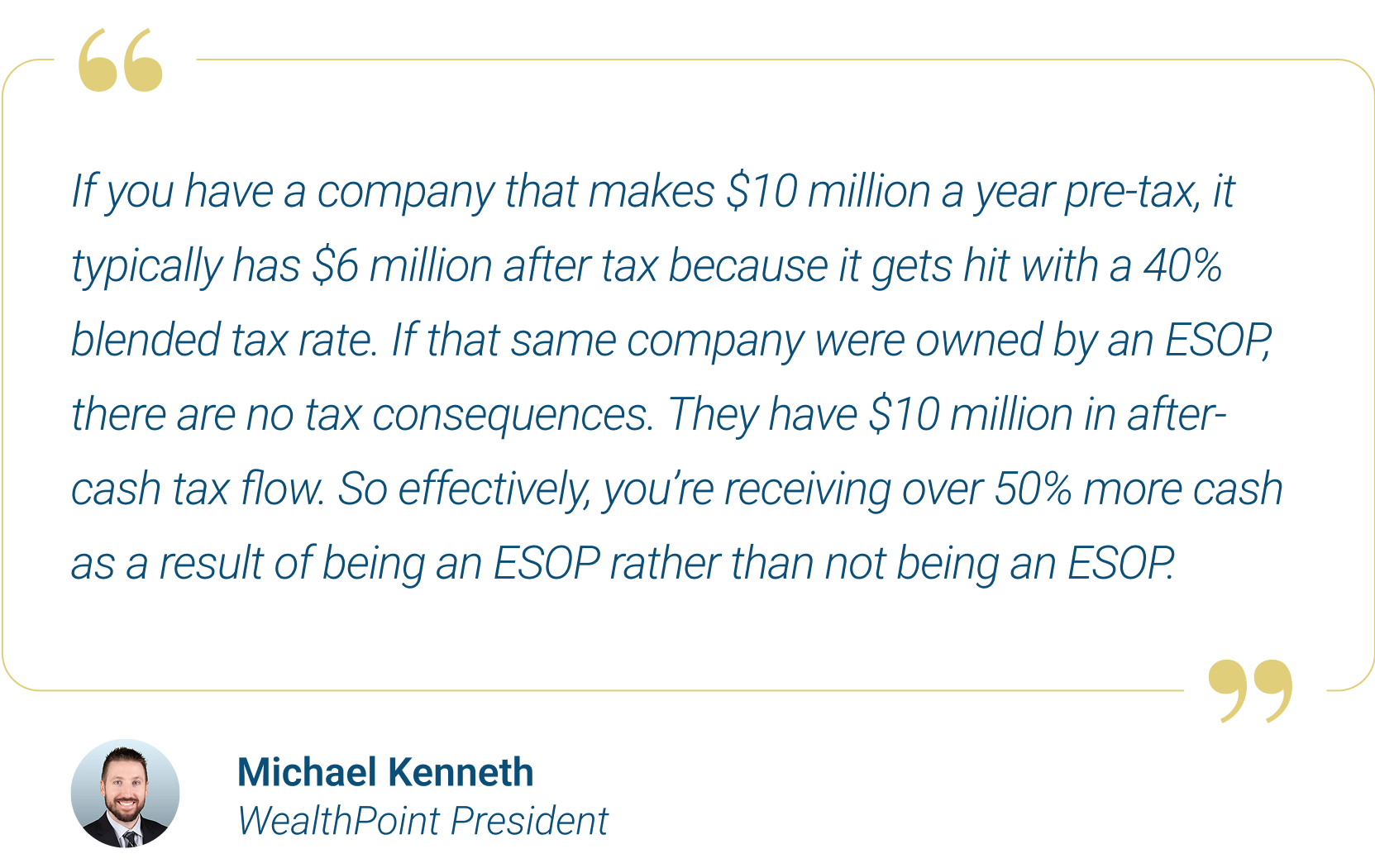

And I don’t think that can be understated, right? So if you have a company that makes $10 million a year, as an example, today it makes 10 million pre-tax, it has, typically, $6 million after tax because we have to distribute out money to pay for taxes on a blended 40% rate.

If you have that same company and they’re owned by an ESOP, it makes $10 million a year. There’s no tax consequences. It’s not making any distributions out to fund tax payment. So if I make 10 million pre-tax, I have $10 million in after-tax cashflow. So effectively, you’re receiving over 50% more cash as a result of being an ESOP than not being an ESOP.

Now, the first few years, we’re leveraging those tax savings to pay off the transaction debt, right? And that’s what really allows the overall process to really take place is we’re eliminating, in some cases, the biggest cashflow hit for a company in the sense of the tax distributions or taxation on earnings. We’re replacing it with paying off debt. But over time, as we pay off that debt, we’re going to have substantial cash flow that’s available for the company to fund future growth, expand geographically, buy more equipment, hire better people, all of those types of things.

Michael Kenneth (27:58)

And oftentimes in really successful lease ops, the amount of cash that they start to accumulate actually becomes a problem, where they have so much cash, they almost don’t know what to do with it, which again, is a great problem to have from an entrepreneurial or a business perspective. The other tax savings piece can happen on the shareholder side.

And so, if we structure the transaction appropriately, we have the flexibility where we can defer taxes by electing what’s called section 1042. It’s very similar to a 1031 exchange in real estate. If you’ve ever seen those where you sell a property and have a certain period of time to reinvest into another property, kind of like for like exchange there, same concept with an ESOP. So if I want to elect 1042, I have to sell my shares directly to the ESOP.

I then have 12 months, technically you have three months pre-transaction, 12 months post-transaction to reinvest into what’s called Qualified Replacement Property or QRP. That shareholder makes that decision and whatever amount that they reinvest or allocate towards QRP results in a tax deferral strategy where they don’t pay any taxes on the overall transaction, right? They’re deferring that tax benefit.

Couple of key points there, that 1042 is simply a deferral. It is not a permanent mitigation, right? And so if I sell my company for 30 million and I take all 30 million and invest into Apple as an example, whenever I sell my Apple shares, I’ll recognize taxes on that. It’s just a carryover and basis. I recognize my taxes on that transaction.

So it’s just a, it’s a deferral strategy. Now, if you have, say, an older client who decides to monetize elect 1042 and they pass away while still holding those investments, you can then get the permanent mitigation of those taxes, right? You get a step up in basis, fully mitigates the tax consequences as a result of that. So a couple of just quick questions I want to interject here. First question, Manny had asked, can this work of a company is in an LLC structure?

Michael Kenneth (30:08)

That’s a great question. So in order to be an ESOP, we have to be a corporation. ESOPs have to acquire shares. They cannot acquire membership interests or membership units. And so if a company is an LLC, we just need to be mindful of that and go through a reorganization either as a part of the transaction or prior to the transaction to convert to a corporation. Depending on the tax situation, meaning, is the LLC being taxed as a C-Corp? Is it being taxed as an S-Corp? Is it being taxed as a partnership? You’ll have different structures there. That can get pretty complex.

There’s also some really unique planning opportunities that can actually happen if we have an LLC that’s taxed as a partnership. Because in that situation, we may be able to get the benefit of both situations by doing 1042 and becoming an S-Corp at some point in the future. We can definitely talk through that in a little bit more detail on that front. But yeah, so you have to be a corporation in order to be an ESOP. That’s very common though, if you have an LLC, you just go through an overall structure, you know, kind of a reorg, if you will, right, to get to that structure. Another question was, do public securities qualify as QRP? Yes, they do. Generally, QRP is stocks and bonds of US based operating businesses, right?

So the initial intention of 1042 was to allow people to sell their company to an ESOP and then take, effectively, the gross proceeds, right? Or the pre-tax proceeds and reinvest into the US economy. That was the kind of general train of thought there. But again, stocks and bonds of US based businesses generally qualifies. If you wanna have a more specific conversation on certain investments or strategies, we can definitely talk about that. And then one of the last questions is just can a 1042 election be used to invest in like a private investment fund or something like that?

In that situation, the short answer would be that we cannot. And the reason why I say that is there’s regulations regarding 1042 in terms of what that investment looks like, how much of the earnings of that investment are passive versus active. That’s a key component there is what qualifies as qualified replacement property. So it kind of depends on what’s in that investment fund and whether or not that qualifies as a result.

Michael Kenneth (32:30)

One other comment on 1042 that I hadn’t hit on yet, but just this bottom down here is in order to elect 1042, you have to be a C corporation. And so if you’re already a C Corp, that’s great. You can easily elect it. If you’re an S corporation, you should really do an analysis of do we want to remain an S and maximize the tax benefits post-transaction, or do we want to convert to a C Corp elect 1042?

But if we go, if we started an S Corp and go to a C, we have to typically wait five years before we go back to S. So there’s pros and cons of each. Most important thing is that we should do an analysis to just really determine what’s the amount of the tax savings, who gets the benefit, and what’s the right result for both the shareholder as well as the company. And I want to just pause there, Drew, and ask a question from your perspective. What would you say the ratio is of companies that decide to do 1042 versus not?

Drew Schaefer (33:31)

Yeah, it’s interesting. It seems to go in waves, of course, with tax policy. And there are some self-satisfied advisors that push it a little more than others because they might have some additional service offerings that help with that 1042 investment. But I would say the majority, maybe only 20% right now are electing that if I had to put a rough number on it.

And a lot of people look at it differently. Some people say, well, if the company can be an S-corp, not pay any taxes, then in theory, I could be paid off on my seller note even quicker than if we had to convert to C. So there’s, to your point, a lot that goes into an analysis to see what makes sense for each seller.

Michael Kenneth (34:30)

Perfect. Yep. And then there was just one last question. And I would actually say, Drew, I agree with you on that, right? I think it is something that’s talked about significantly more than it’s implemented on as a result. One last question, just a comment about S-Corp and C-Corp, and can the same entity do both?

And the answer is, it depends, but — yes, we have seen companies where they decide to elect to be a C Corp for purposes of the transaction, or they’re already a C Corp as an example. They are a C Corp, they transact, allows the shareholder to elect 1042. And then when appropriate, whether right away or if they have to wait a period of time, that five year window, then the company can elect to be an S Corp and really maximize the tax benefits on an ongoing basis.

from that perspective. So the next few slides are tax code provisions. I’m not going to get into all of those, you know, in terms of today’s session. It’s early out here in Arizona and I don’t know that going through each of the tax code provisions is going to be that enlightening. But the overall point that I want to make is just that there are various tax code provisions and rules, regulations, testing requirements, compliance requirements.

That we just want to be mindful of as we navigate an ESOP transaction. In other words, we have to do proper testing, proper analysis on an annual basis, just to make sure that we’re staying in the guidelines and the limits of these various tests, whether it’s 404, 409P, 410, 414, 415, etc. We can definitely dive into more detail on that offline if anybody wants to go through some of those key provisions there.

Board control and governance is another big factor. I mentioned it a little bit earlier. But again, we have a corporation, have to be a corporation to transact as an ESOP or be an ESOP. All corporations have to be run by a board of directors. And so what we do is in the process, we help to determine who’s on the board pre-transaction to go in and enter into the transaction. We also create the structure so that we can be run by the board of directors post-transaction. It varies, but most of the time, I’d say probably 95% or more of the time, the ESOP trustee will want to have an independent director or more, maybe two, three, something like that be added to the board.

But most of the time the ESOP trustee does not want to be on the board, right? So it’s creating a structure where we have a level of independence to help really run the board, oversee the board. But again, we create that structure so that the board is eligible to continue to run and operate the business.

Michael Kenneth (37:13)

One other thing on that is when I say operate the business, the board’s primary responsibility is to make sure that it has the right leader or leaders in the organization to carry out the success of the company. In practical speaking, usually those leaders are the individuals that were selling the shares, right? It’s usually the key shareholder that’s been founded the business, running the business, excuse me, operating the business. And we just want to make sure that they have the right team around them to continue to be successful.

When it relates to board governance, Drew, just kind of a question here. I know in most transactions, we’ve obviously worked on several transactions together. You do not serve on the board, but you want a level of independence on the board. Can you maybe just expand on, know, one, why you don’t wanna be on the board, right? And then two, what is the rationale for the independence or how do you determine that, you know, how many, what level of independence you know, those types of things.

Drew Schaefer (38:14)

Yeah, so my role is, I guess we’ll talk about the need for independent trustees later, but it’s kind of similar as far as if you’re a CFO and an internal trustee, there’s an inherent conflict. And as a fiduciary, I have to put the benefit of the employee owners above my own as part of that definition. So there could inherently be a conflict of interests at the end of the day. And so I do not serve on any boards for any of my clients. I’ve served on other boards, but just to avoid any potential conflict or appearance of conflict.

And there are typically independent directors that can serve much more effectively, whether they’re familiar in the industry, the local community, bring other things that I can’t necessarily specific to that company, but I can still add value from an ESOP perspective, whether it’s administration or different decisions that a board might need to make that they should look at differently once they’re an ESOP company.

Now, it’s not something I vote on. I still don’t have a vote, but more of a consultant in that respect.

Michael Kenneth (39:47)

Gotcha. No, that’s really helpful. And I think that’s critical because like I mentioned earlier, think a lot of, you know, we start talking about ESOPs, the idea of control or the topic of control and decision-making is something that is always top of mind, right? Specifically for privately held business owners that, you know, they’ve never had to answer to anybody, right? As a result of that. And so the idea of I can sell, but I still want to participate. Maybe I haven’t received all of my money yet.

But then I have to answer to somebody definitely creates, you talked about conflict. I think there’s a level of conflict as that result. But like you just went through, it’s really not creating a conflict. It’s more so let’s just make sure that we have proper governance to carry out being an employee owned company. Another key factor on the independent board director process is typically we have a nominations committee at the board.

And correct me if I’m wrong here, Drew, but usually you get candidates that are nominated and you have to select from those candidates to pick and say I approve this one or I don’t approve that one or those types of things. you know the idea of I guess maybe sourcing the independent director or finding that independent director is really up to the current board. You’re more so just picking from the candidates that are being presented to you.

Drew Schaefer (41:02)

Yeah. No different than if you own a stock in a publicly traded company, you get a slate of directors proposed to you and you vote your proportional shares. It’s the exact same concept, except for obviously in the 100% ESOP situation, I’m voting 100% of the shares, but only on the slate that is proposed to me. And if I say, don’t think any of these are qualified, then they would come back and go back to looking for other potential directors.

Michael Kenneth (41:40)

Perfect, perfect. So we have our last polling question, which should be coming up here shortly. Just make sure that you guys answer that to get the CE credit. For the sake of time, I’m just gonna keep running through the presentation here as a result of just making sure we get through all of our slides. One comment I wanna just hit on a little bit is incentive compensation or executive compensation as it relates to within an ESOP context.

As an example there, know, ESOPs are great vehicles. We talked about the wealth transfer aspect of them on a go-forward basis with transferring ownership or value, if you will, to employees. But one comment I want to make, though, is that sometimes that may not be enough for your high-income earners. And what I mean by that is just the fact that, you know, when you’re doing ESOP allocation, there’s all these different tests and provisions to establish a fair allocation of shares.

But if you have your high earners, your executive team, your leadership team, etc., you may want to create more value for them as a result of the overall transaction. And so anytime you’re looking at doing an ESOP, it’s just important to analyze synthetic equity provisions, whether it’s like a stock appreciation rights plan or some sort of like a phantom stock plan structure to allow for the board to really establish these plans and really incentivize those key people, right?

Michael Kenneth (43:03)

Help them see what’s in it for them, help them understand what’s that kind of character, if you will. Also establish the golden handcuffs as a result so that they can receive additional compensation, additional value as the ESOP is operating. And it’s critically important because at that first, in the first few years, because that’s where you’re the most leveraged as a company. You have the most amount of debt, you just became an ESOP, so that’s a new structure. So we just want to be mindful of that.

I would say probably 90% of our plans have stock appreciation rights or some sort of management incentive type plan structure, something in there because we want to create those golden handcuffs and that carrot that’s down the line for them. Another factor of ESOP transactions is warrants. Warrants are very common in ESOP transactions. We’ll hit on the reasons of kind of why they’re common here in just a second, but warrants are effectively a form of a stock option, where we established the strike price today on the value of the warrants or the value to exercise those warrants.

And what they do is they allow the holder of those warrants to monetize, pay that strike price at a predetermined date in the future. Usually it’s either eight or 10 years out or whenever the transaction debt has been repaid, whatever is earlier that takes place. But what it really does is it creates another avenue for the selling shareholder to effectively have a second bite at the apple. In this example here, I’m a numbers guy, so I can more so explain the table than the text up here. But in this example, we have a $35 million company. You can see we have the ESOP owns 150,000 shares. The client or the selling shareholder holds 25,000 shares. So we can see what’s the strike price, what’s the price per share.

At the time of transaction, there’s no value in those warrants because we’re highly levered, right? There’s no real equity value in the company. Over time, as either the value of the company grows, in this case, we’re growing it at basically a million dollar increase on value per year from an enterprise value perspective, or as the debt gets paid down, we can see that the equity value of the company increases. And so if I hold these warrants, I then have the ability to have a second bite at the apple effectively monetize for additional consideration whenever those warrants become effectively in the money, if you will.

Michael Kenneth (45:29)

I think the biggest reason that why we have warrants as a part of ESOP transactions is going back to my comments earlier, the selling shareholder is not receiving all of their money upfront. And so this really is a form of additional consideration to compensate for them for not receiving all of their money upfront.

In addition, what we typically see is the amount of warrants has an inverse relationship to the interest rate on their seller debt. In other words, if I transact and I accept a below market interest rate, right, interest rates today are in the, call it 7% range. So if I transact and my interest rate on my seller debt is 5%, I’m saving the company effectively 2% a year on whatever that balance is. So in exchange for taking a lower interest rate, I would like to see more warrants as a part of the overall transaction and vice versa.

If I want to try to charge a higher interest rate, I should expect to receive less warrants because of that whole time value of money and consideration perspective. The other factor that warrants have that I think is substantial is the estate planning aspect. And so this table here actually looks at a real transaction that we did. You can see the trailing 12 month EBITDA, pretty successful company here. We can see the multiple and the enterprise value.

Then we can see again year one when the transaction took place again, $125 million business, $125 million of debt as an overall structure. So there’s no value really from an equity perspective, right? So there’s some inherent value that’s there, but for practical applications, there’s not a huge value that they’re from an equity value perspective. But over time, as the value of the company grows and as we pay off this debt over the next eight years, we can see that the equity value per share increases substantially. And so from an estate planning context, we can transact, we issue the warrants immediately post transaction at that discounted value. Then we make sure the client gifts those warrants, right? Whether you’re doing multi-generational planning, spousal lifetime access trust, whatever the overall structure is, but we can gift those warrants and then all that appreciation can happen outside of that entrepreneur’s taxable estate.

Michael Kenneth (47:47)

And so again, this is just a great planning vehicle, that’s really just a byproduct of an ESOP transaction. But if you have any clients that you’re helping that are going through an ESOP transaction, and there’s warrants included, we really want to focus on the estate planning aspect. You can see here, this is substantial increases in terms of the estate planning growth and appreciation that can happen outside of a taxable estate.

I mentioned earlier about share allocation. So I wanna switch gears a little bit and just look at the share allocation. This is just an example here of how share allocation could operate or could work. In this case, we’re using a points-based system. So the default provision or the safe harbor provision is to allocate shares based off of compensation. In other words, if my compensation is $100,000 and the total comp for the entire company is $10 million total payroll, then I have 1%, I get 1% of the shares that are allocated.

But in this example here, we can use a points-based system. And so in this case, we’re giving out one point for every $5,000 of compensation, and then we’re giving out 10 points for every year of service. And so we can see, based on this table here of employees, different compensation, different years of service, we can see how their total points are and then how those shares are being allocated.

So as an example, if we compare, say, employee six and employee seven in this table here, employee six only makes 80 grand a year, but they’ve been with the company for 18 years. Employee seven makes $175,000 a year, right? Over, you know, twice as much as employee six, but they’ve only been here for two years. So based on this formula, we can see that employee six is going to get almost a little over three times, almost four times as many shares per this allocation formula as the higher earner.

And so this varies, right? Every company is different in terms of how we wanna allocate shares. Do we wanna focus more on compensation? Do we wanna focus more on years of service? And then subsequent to this, we also have to make sure we test all of this to make sure this is a fair allocation, right? In some situations, we run into some issues, we run into some challenges, and so we have to refine that points-based formula in order to get a fair allocation.

Michael Kenneth (50:05)

I will say that I think the points based formula has become more and more common over the last few years. Specifically, I noticed that during COVID you had obviously like the great resignation, people leaving for more money, didn’t have to show up in the office every day, those types of things. And so this points based system where you’re rewarding comp and years of service is critical because let’s say we have two employees, they both make the same amount of money, but one’s been with me for 15 years and the other one just started yesterday.

If that’s the case, I want to reward more shares to those employees that have been here longer, right? And so it creates the formula where we can allocate shares based off of that and reward people for making more money, i.e. adding more value to the company, taking on additional roles, responsibilities, etc. But we can also reward more people for staying longer, right? Longer tenured, remaining with the company for your entire career, those types of things.

This then, this points-based system or the share allocation also just ties in nicely with the account balance projection. This is just an example from an account balance projection, but the whole intention of this, as you can see after, you know, call it five years, 10 years, 20 years, how did the amount of shares change over time? How does the per share value change? And I think what’s important here is that from a company standpoint or employee standpoint, the more money I make, the more shares I’m going to get, the bigger my retirement account is going to be.

And so again, these are just a sample analysis, but I think it’s critical for companies that are looking to do an ESOPs to always look at what’s in it for the employees. That’s a key factor of becoming an employee-owned company is the legacy component, if you will, of being an ESOP. I can sell to a third party, I can take chips off the table, I can monetize my illiquid asset, but the name of the company is not changing, right? I’m selling it to effectively the employees or the people that help to get the value to where I wanted it to be from a growth and value perspective. I wanna just switch gears a little bit and talk about some kind of current news in the ESOP world.

Michael Kenneth (52:22)

And when I say current, it’s really over the last couple of years. But that’s very current from a government perspective. So there’s kind of two things that have taken place in the ESOP world over the last couple of years. The first one was in August of 23, the IRS sent on a letter that really wasn’t prompted by anything specific. It was more so just a letter that they published and they posted that was really warning against tax avoidance strategies pertaining to ESOPs.

I think from their perspective, they’re just wanting to be mindful that, you know, anytime they have situations where you have tax exempt vehicles, tax deferral strategies, you may have people in the space that are trying to promote, you know, structures that maybe skirt the lines, right, or really hop right in that gray area from that perspective. And so just a couple of the things that are out there in the marketplace just to be mindful of.

Again, I mentioned earlier, I’ll hit on it again. Once you’ve seen one ESOP, you’ve only seen one ESOP. And so there’s always facts and circumstances that maybe govern why a structure is this way or that way. But I think the important thing is just to be mindful of that when you’re talking with your clients and really understanding the overall ins and outs of ESOPs.

The first one there is just unreasonable internal loan terms. As an example, I would say on average, most of the internal loans that we see in the marketplace are probably 30 to 50 years, which I think is fair. It’s appropriate. The reason why is because we have a longer duration. So we always have shares to give out for future generations of employees. We’re really managing that benefit, managing the repurchase obligation. But I have seen transactions where they’re 90 years, they’re 110 years, right, or longer in terms of that internal loan.

And you know, just from a common sense perspective, that’s a very long time, right? To think about that it’s gonna take a century or more to allocate shares. Now there could be legitimate reasons for that, but anytime you get up to that length, we just wanna be mindful of it and need to ask the question.

Drew Schaefer (54:45)

Yeah, and a lot of that, to your point, there’s reasons behind those. Sometimes it’s a very profitable company relative to headcount. And so when you have some of these limitations on contributions, you try to find other ways to get creative, to be able to still have an ESOP.

So at the end of the day, we’re very mindful of those longer terms and what we make sure to do if we go anything over 50 years is that we’re making sure in the language that there’s a minimum benefit that’s very meaningful so that it’s not just unnecessarily stretching it out, but doing what an ESOP is intended to do and giving a meaningful benefit, a retirement benefit.

Michael Kenneth (55:35)

Absolutely. And I think you hit on one of the key aspects, I think, on those longer terms is what’s the benefits projection for those employees, right, at various compensation levels and those types of things. Because like you said, there could be a legitimate reason for that. But what we want to be mindful of is that legitimate reason isn’t just so that we can transact at an exceptionally high value and then comply with the safe harbor rules and regulations, right?

There’s gotta be a legitimate reason from an employee perspective from that front. Excessive use of warrants as well as something that’s been out there, you know, again, every fact and circumstances of an ESOP transaction are different, but we have seen some situations where you have excessive use of warrants. Basically, you’re profiting the seller in an unfair situation relative to the ESOP or to the employees.

So we just want to be mindful of that. And then always the last one here, just over leveraging the business, right? Unfair valuations or terms, aggressive projections, aggressive structure. ESOPs are 100% debt-financed transactions, right? Nobody is coming in with equity into the transaction like you see in a third party sale. So as a result, we have to make sure the company is generating the cashflow that it needs to meet all of its obligations first and foremost.

Real simple example, I tell clients all the time, if you’re making $5 million a year, but your debt payments are seven, that’s a problem, right? That doesn’t result in a good structure as a result of that. And so we just have to be mindful of that. We don’t want to over leverage the business or create a situation where, yay, we transacted at 60 million, but we ran out of cash in year three, right? Or something like that.

And then the other kind of news in the ESOP space is in 2024, actually right before the Biden administration left the office and the Trump administration took over, they posted some draft guidance for ESOP transactions. Now this was something that had been on the docket to really address for a long time.

And they posted some draft guidance, they went through the process of giving with 60 or 90 days to allow for comments to be made and then they were gonna you know, formalize that draft guidance in terms of how ESOP transactions should be structured, right? What does the valuation process look like? What does the negotiation process look like? Who’s responsible for the aspects of that negotiation? What’s the process go through? What should a trustee do? What should a valuation firm do, etc.? And really from an ESOP community, it was something that we all were looking forward to because there isn’t any guidance today, right?

It is, you know, we have I would say, you know, substance based on history of transactions and what a good process looks like, but there isn’t any rules and regulations that say you have to go through it this way. At the same time, I don’t know that the guidance had the intended outcome that the government or the administration was really hoping for, not to mention as soon as the new administration took over, one of the first executive orders was to effectively cancel all of the draft guidance that was in process.

Michael Kenneth (58:49)

So we’ll see what happens going forward. But curious Drew, just from your perspective, because I think that, you know, from my view, the draft guidance was more focused on the trustee team than some, than maybe the selling shareholders, right? Of really the roles, responsibilities, fiduciary responsibilities, et cetera. Curious to your reaction to it. Again, knowing it’s not in law, it probably won’t be for a while, given how long it took just to come up with this draft guidance, but just curious to your reaction to it.

Drew Schaefer (59:20)

I think from the trustee community, pretty disappointed with it, I guess at the end of the day. So if it was going to move forward, there was definitely going to need to be some tweaks on that. I think the good news is, as of last week, the new administration’s nominee for Assistant Secretary of Labor and head of the Employee Benefit Security Administration, Daniel Oranowitz, I believe, came out and said that basically he was going to stop the DOL’s war on ESOPs.

Congress, bipartisan, very in favor of ESOPs and the DOL for the various elements that you kind of referenced earlier, be it war and such, valuation. They tend to nitpick on little pieces and it’s more about process than anything and so I think getting more comprehensive support for ESOP structures and the guidance to ensure that we’re all doing good processes, good transactions to have sustainable ESOPs. I’m hopeful that there will be a more concerted effort, more progress, hopefully in this administration.

Michael Kenneth (01:00:45)

Awesome, perfect. So when we look at kind of an ESOP process, this just gives a high level example of the typical process and how long things take. On average, most ESOP transactions are usually a five to seven month long process. The more complex transactions can maybe take a little bit longer. In some situations, you might have a little bit more straightforward transaction or maybe like a minority interest transaction, something like that where it can be a much shorter time horizon as well.

And when I say much shorter, maybe four months or something like that. But I think the important point is that anytime you’re going through a sale, this is no different than a third party sale, right? You have to go through proper due diligence, proper negotiation, documenting the transaction, and then obviously closing. But the comment I would make is that it is a more structured process, right? Where you are really controlling the timing of things, you’re going through the process, defining those kind of gates and timelines.

And as I mentioned, it’s a debt-financed transaction. So you’re not worried about an investor coming in and providing capital or anything like that, or raising funds to facilitate the purchase price. It’s really a debt-financed transaction. When we kind of break down the different phases of what an ideal ESOP process looks like, we go through six phases effectively here.

The first phase is just the discovery process. So feasibility analysis, discovery, understanding what’s valuation range, what are the proposed structure going to look like. And this is all should be done primarily just with the client directly, right? With its sell side advisor and understanding what are the overall term and structure of an ESOP. At that point, assuming all looks well and the client wants to move forward, you then move into the different phases of obtaining debt and analyzing debt.

You go through the engaging and evaluating of the service professionals and the overall due diligence process. We’ll have Drew speak in just a minute here on kind of what that process looks like from a trustee side. And then legal documentation, right? Once we’ve agreed to the overall transaction, we have to document it. The ESOP plan document, the purchase agreement, the transaction documents, et cetera. You then move into the most exciting part for the seller, which is closing, right?

Michael Kenneth (01:03:02)

Receiving the funds that close or the overall, you know, announcing it to the employees, announcing it to the public that you become an ESOP-owned company. And then one of the aspects that we think is often forgotten, but is critical for employee-owned companies is to have a level of post-closing service from various service professionals, meaning from the trustee team, the valuation team, but also on the company side to really guide them through that process.

Once you become an employee-owned company, there’s a certain form and structure and role and responsibility that the company needs to really manage. And so anytime your client is looking at doing an ESOP, you want to be mindful of that because oftentimes they don’t know how to be an ESOP, right? They don’t know how to be an employee-owned company. And there’s different, you know, the funding, the contributions, the board governance, financial reporting, etc. And they usually need somebody to help guide them through that overall process.

So with that, I want to just hit on real quick kind of what a ideal client looks like for an ESOP. We, you know, I think personally, I’m a big fan of ESOPs. I know that Drew is as well, but not all companies can be or should be ESOPs. There are some, you know, structure that I think you want to make sure that you maintain if you’re going to be an ESOP or considering an ESOP. First one is just some financial metrics. You know, personally, I think in order to be a good ESOP, you need to have, first and foremost, consistent profitability.

Again, hitting on my point earlier, anytime you’re a debt-financed transaction, if you have profitability that goes up and down, that doesn’t work very well if you have a fixed debt payment, right? Or a fixed obligation to the bank, to the sellers, maybe a combination of both. And so we generally target companies that are making $2 million or more in EBITDA or profit. There are smaller ESOPs than that.

But when you compare that with maybe fees incurred to do the transaction, the ongoing compliance fees, those types of things, sometimes it can be difficult to do an ESOP at a lower level than that. Not saying it’s off the table. We’ve done ESOP transactions with lower profit companies, but I think that 2 million is kind of the bottom of the threshold there to really have a substantial ESOP. We put in revenue at 20 million as well. Again, that all depends on the profitability.

Michael Kenneth (01:05:24)

I think profitability is more important than revenue when you’re considering an ESOP transaction, but just kind of a number for you guys to use. Number of employees, we generally like to see 25 or more employees. You can do ESOPs with less than that, but you run into some testing challenges as a result, so if you have less employees than that, you always need to be mindful of doing the pre-transaction compliance testing to make sure that you can be a sustainable ESOP going forward.

And then we just listed a few different industries that are very common in ESOPs, manufacturing, distribution, services. We’ve actually seen more professional services recently, accounting firms, law firms, architectural firms, engineering firms, etc. And then construction is a huge component for ESOPs. I would say probably 50, 60% or more of all ESOPs, new ESOPs are happening in the construction industry.

We would like to see more manufacturing or distribution, it kind of ebbs and flows with the market, construction pretty much not, or, you know, it has a majority of, you know, new ESOPs or existing ESOPs. So with that, I want to kind of get to a little bit of a Q&A session with you, Drew, just from an independent ESOP trustee perspective, right? We’ve hit on a few of these questions as we went through the presentation.

But just to kind of kick things off, and I think I know your answer to the first one, considering you have a job and it’s a firm that provides these services, but from your perspective, are independent trustees necessary or maybe secondarily, why are they necessary in any SOP transaction?

Drew Schaefer (01:07:06)

Yeah, so speaking for transactions, think there’s not a sell side advisor that I’m aware of that would advise their client to use some sort of internal. So I think really that’s become the standard these days. So actually one of my colleague trustees was actually an internal trustee for a transaction back in 2004 minority. And he was the least conflicted.

But when you say it like that, least conflicted, there’s still an inference of conflict. So whether to your point earlier with the CFO and CEO, whether it’s an appearance or in fact, there’s inherently going to become issues in a transaction that would make it hard for the internal trustee to really fulfill that fiduciary role and where they have to put the participant’s interest above their own.

And so for transactions, it is the standard. And historically, there were a lot more internal trustees ongoing in that maybe they did a transaction even if they had an external trustee and then they would bring that in-house. And we’ve gotten a lot of opportunities.

So let’s say that same CFO 20 years ago learned about the ESOPs and has been the internal trustee and doing the administration. Well, when that CFO goes to retire, then his or her replacement says, well, I don’t know anything about ESOPs. I don’t wanna be a fiduciary trustee. And we get a lot of calls for that at the end of the day.

But I think the the biggest issue that we’ve seen in those engagements is they’ll say, well, we hired a third party appraiser and they were the experts. So we thought that we relied on their work. Well, the trustee hires an appraiser, but ultimately they are setting the share price. They are negotiating the deal. And so if you’re relying on a third party and don’t have any context or anything else to compare it to, you’re just not in a good position to take on the level of risk that you are as an individual trustee.

Michael Kenneth (01:09:32)

Perfect, yeah, no, absolutely. And I think, you know, hit on some really good points there that I think are potentially misunderstood, right? Of the idea of that fiduciary level of responsibility and that that absolutely exists in a ESOP transaction with a board and that structure. And it’s not as simple as, well, I think my company’s worth 50 million. So that’s what we’re going to transact that, right?

There is that level of independence that needs to happen. And there’s a fiduciary responsibility to see that out. So I’m gonna, we talked a lot about the role that you play, you know, in terms of oversight and the voting capacity and you don’t have the votes or voting capacity on the board, but I wanna maybe just skip over that real quick. You mentioned about hiring a third party valuation firm. I touched on, you know, the fairness opinion, the, you know, purchase price negotiations, those things. What does that process look like on a transaction on the trustee team side?

right? Because I, you know, I went through it more from a sell side advisor side of how we go through the process, but obviously there’s different things that you’re looking at as well, not just, this a fair price for the business? So.

Drew Schaefer (01:10:47)

Yeah, so my process is once I’m engaged for a transaction, looking at the industry location, anything special and nuanced about it, and engaging evaluation firm and legal counsel to represent me in the transaction.

And so we work with very regularly 10 to 12 valuation firms that our experts in ESOP valuations have worked in all sorts of industry. We make sure that everybody has the right capacity to meet the transaction timeline. And then we get into diligence. So there’s obviously financial diligence. You mentioned having a good track record of profitability. So looking back five years, understanding on the industry backlog or the work in progress that’s gonna really support the future looking projections because that’s what the ESOP is buying, not past performance, but future cash flows at the end of the day. So we have to get very comfortable with the company’s financials and really the special sauce that creates that value for the company.

At the same time, making sure we understand legal structure, understanding all the contracts, leases from that side as well to make sure that we know what the ESOP is buying. And so once we digest that, then we have an onsite diligence meeting, meet the sellers, leadership, see the facilities.

There’s some times that there’s nothing to see, especially as more companies have a remote workforce. So if it’s a service organization, there might not be anything to visit, but typically if it’s a manufacturer, there’s facilities, warehouses, etc. to see — if it’s very asset intensive — that’s a factor in the value. We want to make sure that it exists. So after that on-site, and that’s when the valuation firm is creating their valuation report. And so value is a range.

These are companies that are not traded on a daily basis. So they give me a range to negotiate from because really I’m looking at purchase price in the context of everything else, the financing terms, the corporate governance, all those different elements because the ESOP cannot pay more than fair value but all terms of the deal also have to be fair to the ESOP so that there’s no ability for there to be related party elements that take that value away from the ESOP, for example.

And so once we have that to negotiate from, then there’s a back and forth, it’s an arms length negotiation, opposite sides of the table to come to hopefully what results in agreed upon transaction terms and then to your point earlier, then we go to documenting that and that’s just having all the legal documents really reflect what’s already agreed upon. And then as part of that process, I’m also documenting my compliance elements as far as how I got comfortable with that. The ESOP is not paying more than fair value. My process in evaluating the valuation report. The statute of limitations is six years for these, so if there was something to come down the pipeline and six years questioning the transaction, then we have a stack of files that we can easily hand over and get through that process.

And so then once we get that, then we move to close. So see, on average, it’s a 90 to 100 day process. And then we moved into an ongoing role ideally after that.

Michael Kenneth (01:15:01)